Structural Forces at Play in Guiding Child Development

Spotlights ·Interview by Maedbh King

Monica Ellwood-Lowe grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and attended Stanford, where she majored in Psychology.

She is starting her third year in the psychology graduate program at UC Berkeley where she studies

developmental psychology. She is supervised by Profs. Mahesh Srinivasan and Silva Bunge.

What drew you to developmental research?

The honest answer is some combination of interest and random chance. I stumbled into Professor Anne Fernald’s lab after taking an undergraduate seminar with her, and spent some of my most formative research years learning about language development from her and Dr. Virginia Marchman. Once you develop the kind of depth of knowledge in a topic that they helped me cultivate, it tends to follow you around. But what keeps me in developmental research is walking into kindergartens in Oakland and seeing kids’ bright eyes. It feels like a time when you can really make a difference in someone’s life.

Some of your work thus far has explored how childhood environment (with a particular focus on SES) shapes important facets of cognitive development as well as brain development. What are some of your key findings?

As researchers who want to understand how the environment affects brain development, it’s tempting to simply split kids up according to whose parents are highly educated with well-paying jobs (high-SES) and whose parents are less so (low-SES) and measure behavioral and neural differences between them. Inevitably any difference you find will get translated and reported as a deficit for the low-SES kids. There are endless problems with this: What exactly are you measuring when you measure SES? What are the specific environmental mechanisms acting here? What are the structural constraints kids are up against, and who defines “optimal” outcomes? And, intriguingly for me, what are the benefits and trade-offs of different trajectories of brain development? It’s startling when you realize just how much of our knowledge about brain development comes from wealthy kids with highly educated parents who live near universities and have the time and resources to participate in research.

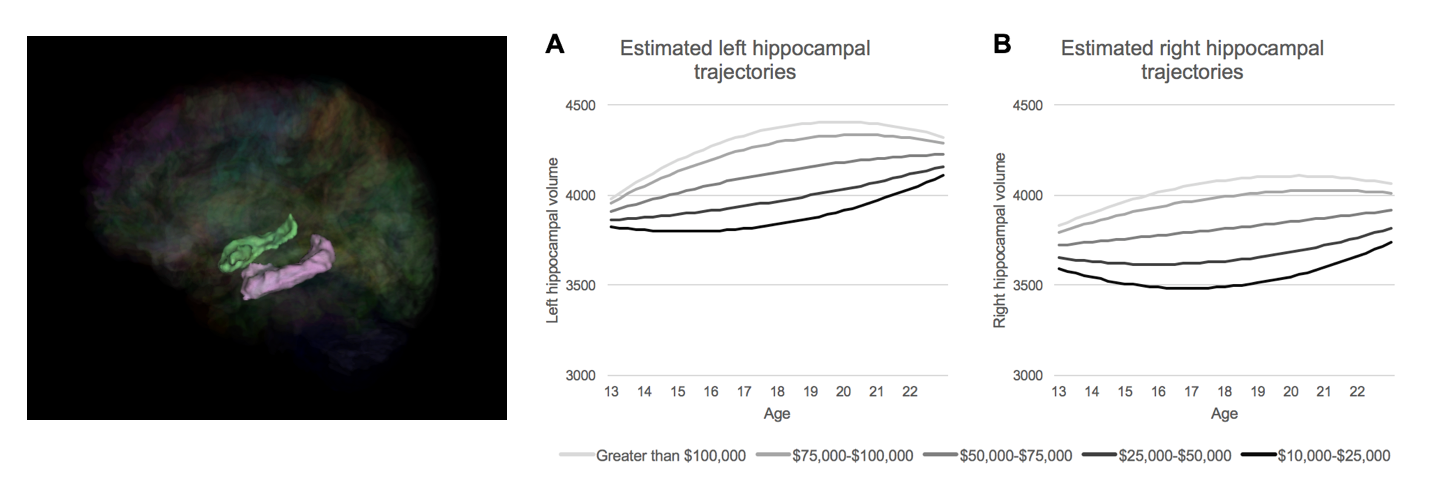

In some of my work, I’ve found that the volume of the hippocampus, a stress-sensitive region of the brain that is central to learning and memory, varies in size across adolescence in a different way for girls whose families make more or less money. For girls whose parents are wealthier, the hippocampus takes the trajectory of development that we are used to seeing in the literature, with a peak around age 18, followed by a plateau. But for girls whose parents are less wealthy, a different pattern emerges, with peak hippocampal volume seemingly appearing later on. Even more interestingly, this finding is independent of their mothers’ hippocampal size, suggesting that it is not mediated by genetic or potentially even shared environmental influences. This raises more questions than it answers. What do different trajectories of brain development mean for learning? What is the cause?

In ongoing work with Professors Silvia Bunge and Mahesh Srinivasan, I’m specifically measuring aspects of children’s home environment that we think might play a role in brain development, like the language surrounding a child during a typical day, and looking at how these relate to children’s attention, learning, and memory. I’m interested not in characterizing one set pattern of “optimal” development, but rather characterizing how development unfolds given the environmental context a child happens to grow up in. What is adaptive for one child given their context may be totally maladaptive for another. We can’t blindly assume the white upper-middle class context and developmental trajectory is optimal.

How do you think your findings have the potential to inform public policy, education or early-life programs?

For one thing, if we accept the idea that children develop skills that best suit the demands of their environment—something which makes sense from an evolutionary perspective—it becomes very clear that schools typically start by building on the skills cultivated in higher-SES environments. Part of this is because there is less empirical research documenting the skills cultivated in lower-SES environments, a gap I’m hoping to fill with my research. And of course, part of this is because of the way schools have been purposefully structured in the first place.

At the same time, there is no question that being in an environment where you are systematically deprived of resources and opportunity for advancement has negative consequences. For example, in research that has been submitted for publication, Ruthe Foushee (another PhD student in the department), Professor Mahesh Srinivasan, and I have found evidence that financial constraints actually cause parents to talk less with their children. Even within a single family, we’ve found that parents talk less at the end of the month—when families are typically the most financially strapped—compared to the rest of the month. What is striking about this is that people tend to think of parenting as a skill that is stable within individuals, but simple fluctuations in external constraints seem to make a significant difference.

I see this contributing to education and public policy in two ways: The first is that we need to stop thinking of development as having a clear pattern and instead think of it as an accumulating series of cognitive and biological tradeoffs. The second is that if we want lower-SES families to behave like higher-SES families, we need to be prepared to give them the external resources—financial and otherwise—that higher-SES families have.

Finally, what advances would you like to see in your field in the next two decades?

I’d like to see a more nuanced understanding of how variation in the environment leads to variation in the brain and behavior of children—with all its pros and cons—and how external constraints affect not only children but their parents and the ways their parents parent. Our focus is so often on individuals, but I’d like us to pay more attention to larger, structural forces at play.

I would also like to see an integration of research on SES and development and research on racism and discrimination. Many people who study SES totally shy away from issues of race, which is bizarre when we consider the enormous racial wealth gap, and the fact that much of our present-day research on SES differences is actually rooted in historical research on supposed racial differences. In my view this is partly because the field of psychology, and cognitive neuroscience in particular, hasn’t figured out how to reconcile with its racist history; because biological determinism is still embedded in scientists’ collective beliefs even if their politics tell them not to say so out loud; and because there is a lack of shared understanding of the ways race has been constructed socially as opposed to biologically. It’s a tricky thing to study but I hope we can work together to try.